Ever since I saw Cloverfield in theaters twice over opening weekend, I have had a soft spot in my heart for the found footage, shaky cam subgenre of horror film. I still firmly believe that when they’re done right, they can be profoundly interesting takes on typical horror iconography, scary for their implied, supposed realism and the way this realism necessitates that we don’t see more than our civilian videographer would. But what makes a good found footage film? For one thing, it can still be effective and innovative at times, and that is why I still want to advocate for it.

First, let me just say however that I haven’t seen Blair Witch Project in many years, but I know enough to retrospectively argue that this film was the game changer. I think more so than even filmmaking though, it changed marketing. When marketing materials for Cloverfield first surfaced, the movie didn’t even have a name, just the terrifying image of a headless Statue of Liberty.

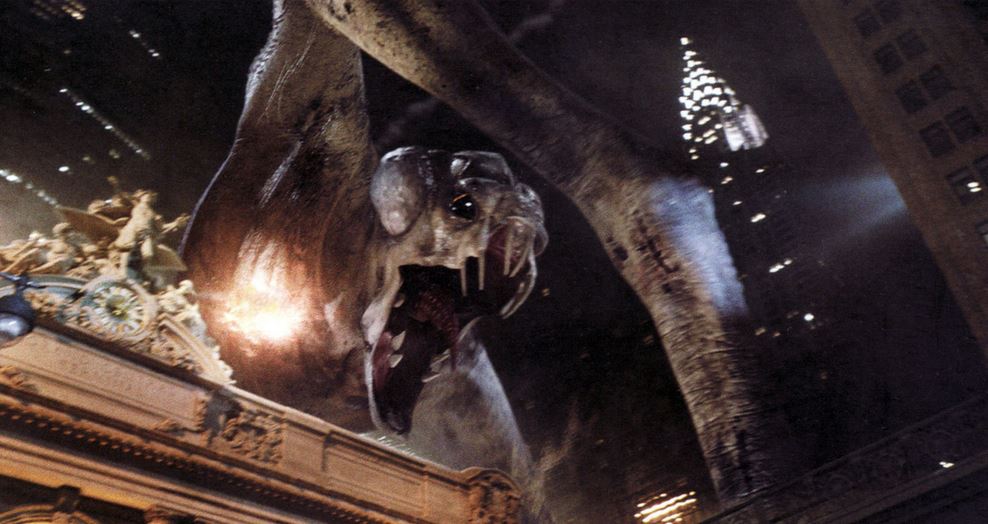

Cloverfield itself really stuck with me, as I said. To this day it remains one of my favorites; aligning ourselves with a specific character’s POV and obscuring our view of the creature in what arguably is a monster flick at its core was both fascinating and frustrating. It probably sounds trite after so many films of its kind have followed suit, but feeling like were there experiencing the horror even while cognitively knowing the horror was strictly cinematic in nature (whereas many people had been led to believe Blair Witch was real) is part of the fun and what made the horror that much scarier for a viewer, in my opinion.

Now, I know the anti-Cloverfield argument all too well: the fact that an endlessly shaky handheld camera and its often dizzying, imperfect movements gave many people headaches. That is fair, but the found footage subgenre has proliferated into something much more multi-faceted, or at least capable of such variety, in more recent years.

For instance, I think 2012’s Chronicle was one of the most captivating uses of this style. It drew footage from a personal handheld camera (which our main character, Andrew, played to creepy, cold perfection by Dane DeHaan, sometimes levitates and moves hands-free thanks to his newfound telekinetic powers that become the crux of the film’s conflict) as well as surveillance video. I applauded this film’s daring and dynamic experimentation with this form, and the way this form was not separate or extraneous: it was emotionally and narratively important for us in understanding these teenagers and the very real evolutions they were going through.

This brings me to V/H/S. This horror anthology has been seen as hit-and-miss when it comes to using the found footage style, but I really enjoyed the mixed bag of tales and terrors told through these means. One segment didn’t fully explain to us why or even how what we were seeing on video was recorded (given that it was an online video-chat), and while this was on one level confusing, it was also the most interesting take on the formula among 6 separate fragments that all, in one way or another, tried to do something different with it; I’d never been so shocked at a twist ending, and it wouldn’t have worked nearly as well in longer form or without the presence of those two recognizable little boxes for our character’s faces to be communicating from within.

And finally, I suppose I have to mention what might just be the titan of found footage—Paranormal Activity. Having seen and enjoyed the first three installments, I couldn’t bring myself to see the fourth. I felt like the now-franchise was taking what made it so original and scary in the first place and turning it into, well, a franchise—fraught with boredom and a sense of going through the motions.

Now, with The Marked Ones spin-off coming out soon, I can’t help but find myself itching for something different. I loved the way the third film played with older video technologies to fit into the prequel slot of the tale’s timeline. And I even thought that the second film did some creative things with camera placement that made it a creepy and worthy sequel.

But that is precisely the trick, isn’t it? If we start to see found footage as just another worn-out horror convention in itself, without ever striving to do anything new with it, then there is no point in making horror films in this way anymore. The point of found footage, to me, is to take horror conventions and film them in a way that we never could before the advent of portable and mobile technologies—camcorders, cell phone video, surveillance video, etc— making these films specifically even more pertinent to our times and above all, unique to watch.

And as a side note, I think there is a reason this form fits the horror and sci-fi molds better than other genres. Teen party/sex comedies like Project X and The Virginity Hit more or less flopped, and my opinion as to why this is has to do with the fact that those are things we can probably experience and therefore film ourselves.

When it comes to horror and science fiction though, it is precisely the blend of realistic style and frame narrative (mainly, the answer to why someone is filming the events in the first place) and something totally unrealistic, supernatural, and, of course, terrifying, that makes the found footage format work at all. I still defend it because when it works, it really works. The catch is, we can’t grow so complacent that we assume it will work on its own merit, without any experimentation, creativity and work of our own as filmmakers and filmgoers alike.

Sara majors in Film Studies and Media & Communication at Muhlenberg College. Her favorite genre is horror but she loves learning, writing and talking about all kinds of movies and all forms of entertainment. She has interned with Film Forum and Tribeca Film, both in her native NYC where she hopes to find work in criticism, marketing, distribution, or festival programming post-grad. Her blog and associated Twitter were created with the intention of being more involved and aware of happenings in the film and television industries, as well as to practice writing about pop culture in an academic but friendly and funny way.